When NBA Teams Show Their True Colors: Four Decades of Data Reveal When Teams Really Become Themselves

Analyzing 1,300 seasons reveals surprising patterns about team development - and challenges everything we think we know about early-season basketball

A few weeks ago, I found myself digging through Milwaukee Bucks box scores, trying to pinpoint exactly when teams reveal their true identity. That research spawned something I called the "True Bucks" metric (as detailed in last week’s post) - a simple way to identify when a team starts consistently playing like their final record suggests they should.

But one franchise wasn't enough.

The patterns were too intriguing to ignore. If the Bucks showed clear patterns of when they became "themselves" each season, what about the rest of the league? Do some franchises consistently take longer to find their footing? Do others show us who they are right away?

So, I expanded the study. Every NBA team. Every season since the NBA-ABA merger in 1976. I looked at over 1,300 seasons of data, each telling its own story about when a team's true identity emerged.

What I found challenges much of what we think we know about early-season basketball. It suggests that some of our most basic assumptions about team development - about market size, about conference differences, about good teams versus bad ones - might be completely wrong.

The results tell us something fascinating about when we can trust what we're seeing on the court. More importantly, they reveal how the NBA's evolution over four decades has fundamentally changed how teams develop their identity.

Let me show you what I found.

Part I: From True Bucks to True Team

Let's start with the obvious question: what exactly are we measuring here?

The concept is simple, even if tracking it means digging through thousands of box scores. We're looking for the first point in each season where a team starts consistently playing at their eventual season-ending level. Specifically, when do they first match or exceed their final winning percentage in three out of four consecutive games, after having played at least eight games?

Take the 1985-86 Celtics, for instance. They would finish the season with a .817 winning percentage - one of the greatest teams in NBA history. But when did they first start playing like that historically great team? When did the real Celtics emerge? It was November 20th, 1985, to be exact.

If you're thinking this sounds somewhat arbitrary, you're not wrong. I could have looked for two out of three games, or four out of five. But after analyzing decades of data, three out of four captures something real - a strong enough stretch to suggest actual performance rather than luck, while allowing for the occasional off night that even great teams have.

The eight-game minimum is equally deliberate. You need some kind of baseline sample size before declaring any stretch "real," and eight games - about 10% of the season - feels right. Any earlier and you're chasing statistical ghosts.

Here's what we found scanning nearly half a century of NBA basketball:

The median time for teams to reach their "True Team" point? Just 11.5 games.

The average? A much higher 22.4 games.

That gap between median and average tells us something interesting about how NBA teams develop. Most teams show us who they are relatively quickly - hence the low median. But some teams take so long to find themselves that they drag that average up significantly.

Think about what this means for how we watch basketball. That 11.5-game median suggests that for most teams, we actually can start drawing meaningful conclusions pretty early. By Thanksgiving, we usually know what we're looking at.

But those outliers - the teams that take 40, 50, sometimes even 70 games to play consistently at their final level - they tell us something else entirely. They remind us that team development isn't always linear. Sometimes it takes until March for a team to really become itself.

The question is: what separates the quick developers from the late bloomers? And perhaps more importantly, has this pattern changed as the NBA itself has evolved?

Part II: A Tale of Two Numbers

Let's talk about what makes the gap between our median (11.5 games) and average (22.4 games) so wide.

When I first saw these numbers, I assumed I'd made a mistake. How could the median be nearly half the average? The answer lies in some fascinating outliers that tell us more about NBA team development than any statistical average could.

First, there's the consistency of that median. Season after season, regardless of era, regardless of team quality, regardless of market size - teams tend to show their true identity around the 11-12 game mark. The Philadelphia 76ers of the early '80s, the Chicago Bulls during their dynasty years, the Warriors during their 2014-19 championship runs - all typically revealed themselves right around this point. Even the 73-win Warriors team of 2015-16 showed exactly who they were by game 11, starting 11-0 and never looking back.

But then there are the outliers. Oh boy, are there outliers.

Take the 1978-79 Bucks, who took an astounding 79 games before consistently playing at their season-ending level. Or the 2000-01 Bucks, who needed 75 games (which you can read more about in my deep dive from last week).

These aren't just statistical anomalies - they're examples of teams that spent almost entire seasons searching for their identity.

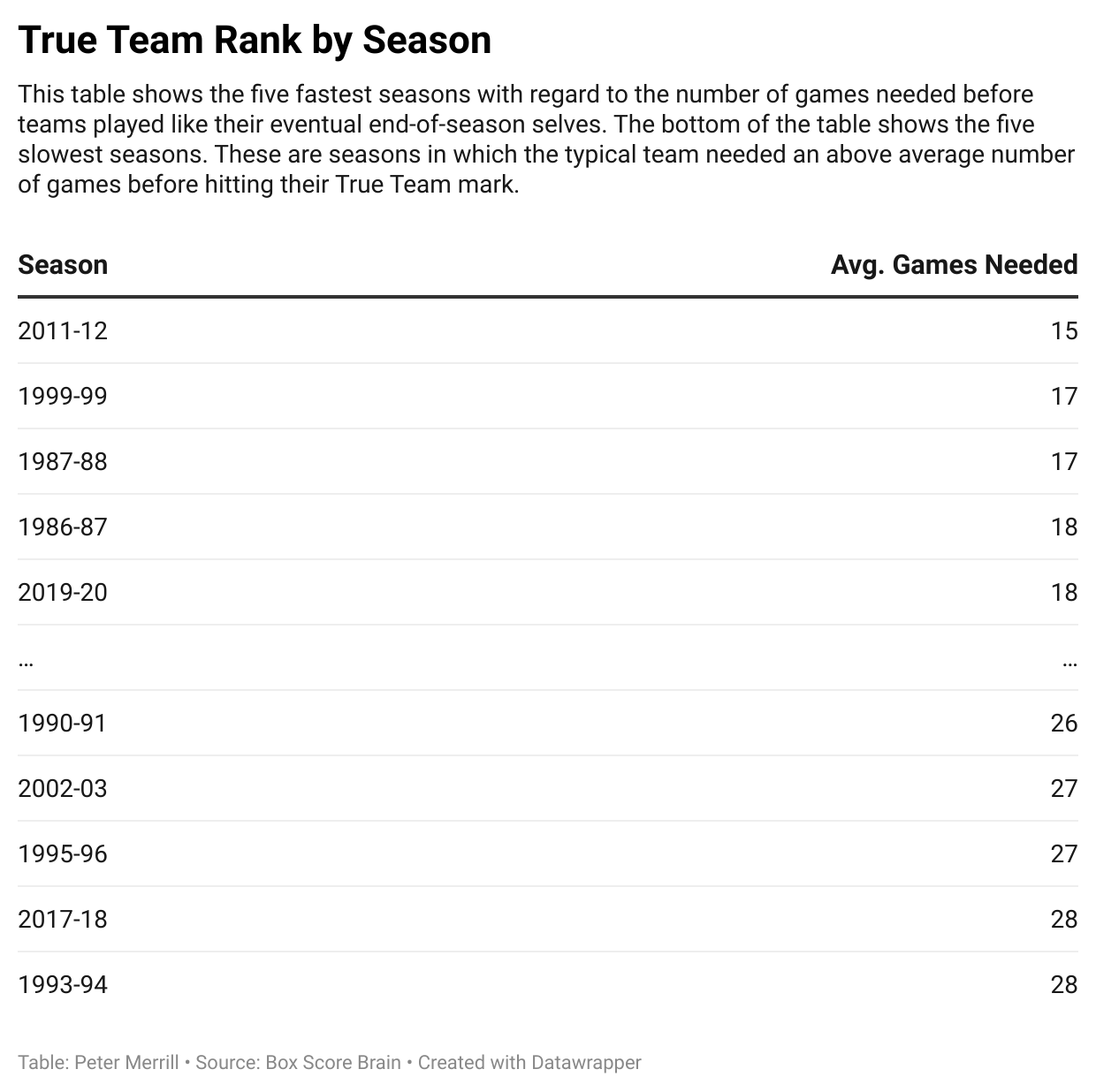

What's interesting to me is how these late-blooming seasons cluster. The early 1990s saw teams taking longer to find themselves - an average of 24.25 games compared to 21.41 in the pre-1988 era. This wasn't random. The NBA had just undergone its largest expansion in history, adding four teams in four years (Charlotte Hornets and Miami Heat in 1988, Minnesota Timberwolves and Orlando Magic in 1989). With 27 teams now competing for the same talent pool, rosters were thinner, matchups were less familiar, and team development became more unpredictable. The physical style of play and influx of new talent during this era only added to the uncertainty.

Then there's the other extreme. During shortened seasons (the 1998-99 lockout year, the 2011 lockout, and the COVID-interrupted 2019-20 season), teams showed their true identity very quickly - averaging just 16.78 games. When you have fewer games to work with, apparently you figure things out faster.

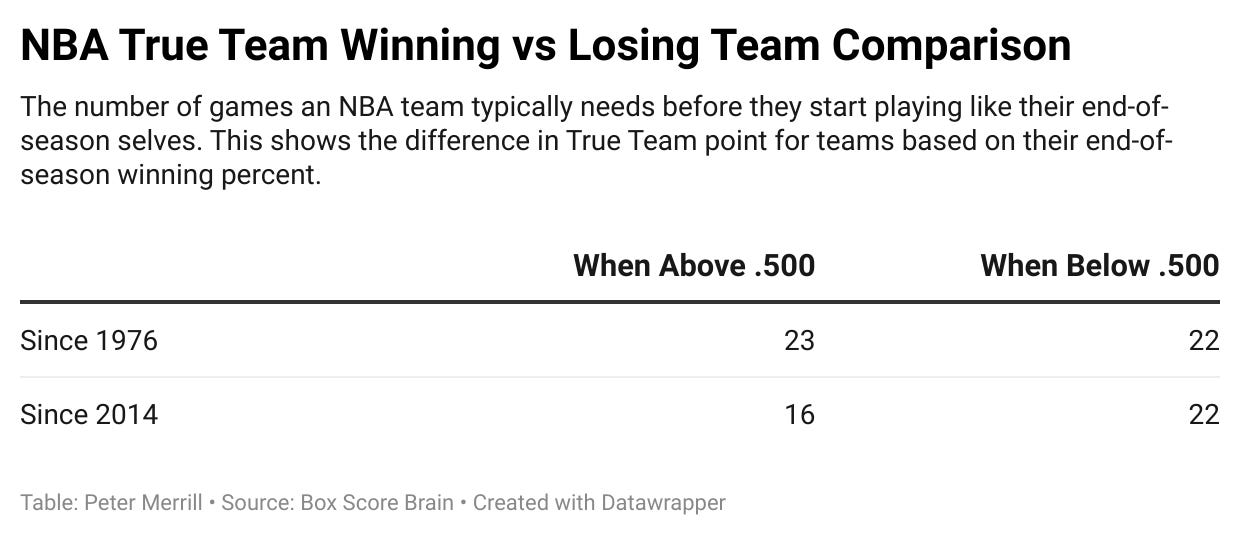

But here's where things get even more interesting. For most of NBA history, good teams and bad teams followed similar development patterns. Since 1976, teams that finished below .500 needed about 22.14 games to show their true identity, while winning teams needed 22.71 games. The path to mediocrity took just as long as the path to excellence.

That said, something has changed dramatically in the last 10 years. Since 2014-15, teams finishing above .500 have shown their true identity much faster - averaging just 16.07 games. Meanwhile, losing teams have remained consistent with historical patterns, still needing about 22 games.

Think about what this means for how we watch basketball. When a team starts hot in today's NBA and maintains it through 16-17 games, history suggests that's probably who they really are. But when they struggle early? That same history tells us we need to be more patient - those teams still typically need the traditional 22-game sample size before revealing their true identity.

This isn't happening by accident. The rise of analytics departments, sophisticated tracking data, and AI-powered analysis means teams can identify their strengths and weaknesses faster than ever. What once took 20+ games of film study can now be gleaned from detailed statistical analysis after just a few weeks.

The 2017-18 season offers a fascinating exception to this trend. That year saw an unprecedented 20-game median and 27.50 average before teams showed their true identity - the highest combined marks in my dataset. I think it was a perfect storm: the three-point revolution had reached new heights, teams were still adjusting to the pace-and-space era, and several contenders had undergone major roster overhauls (like Cleveland trading for Isaiah Thomas, or Oklahoma City incorporating Paul George and Carmelo Anthony). Even the analytics couldn't speed up development when the very nature of how basketball was played was in flux.

The numbers tell us something else too - something that challenges conventional wisdom about how NBA teams develop. But to understand that, we need to look beyond league-wide trends to see how individual franchises tell their own unique stories...

Part III: The Franchise Factor

Not all teams are created equal when it comes to finding their identity. Just ask Denver Nuggets fans.

The Nuggets consistently show who they are faster than any other franchise in the league, needing just 16.1 games on average to hit their "True Team" mark. The Portland Trail Blazers (17.5) and Milwaukee Bucks (17.6) aren't far behind. These aren't just recent trends - they're organizational patterns that have persisted across decades.

Denver's quick emergence makes sense when you look at their organizational philosophy. Since the Doug Moe era of the 1980s, they've consistently played a distinctive style: high-altitude, up-tempo basketball built around versatile big men. Whether it was Alex English, Antonio McDyess, Carmelo Anthony, Nikola Jokić, or anyone in between, the Nuggets have always known exactly what kind of team they want to be. They might not always be good, but they're always decisively themselves - hence the consistent development timeline whether they're winning (14.3 games) or losing (16.1 games).

At the other end of the spectrum sits the New Orleans Pelicans, requiring a league-high 29.8 games to reveal their true identity. The Chicago Bulls (28.3) and Charlotte Hornets (27.5) follow close behind in the slow-development club.

What makes these differences interesting isn't just the gap - it's how consistent these patterns are within each franchise. The Nuggets are quick to show their identity whether they're good (14.3 games in winning seasons) or bad (16.1 games in losing seasons). They are who they are, and they don't take long to show it.

The Pelicans tell a different story. Their overall average of 29.8 games masks a shocking split: they need 37.9 games to reveal themselves in losing seasons but just 17.6 games when they're good. When things are going well in New Orleans, you know it pretty quickly. When they're not? Better settle in for a long wait.

What makes this Denver-New Orleans comparison compelling is that they're both smaller market teams. If market size determined how quickly teams found their identity, they should show similar patterns. But they don't - which led me to look at market size across the entire league.

The data reveals something surprising: market size has virtually no impact on team development. Large market teams (22.76 games), medium markets (22.73), and small markets (22.67) are virtually identical in their development patterns. The bright lights of New York or LA don't seem to speed up or slow down the process of finding your identity.

Even the historic East-West divide barely exists when it comes to team development. Eastern Conference teams need 22.3 games on average, Western Conference teams 22.5. The geographical balance of power might shift, but teams in both conferences take about the same time to show us who they really are.

These patterns tell us something important about NBA franchises. The speed at which teams reveal their identity isn't about market size or conference affiliation - it's about organizational DNA. Some franchises, for better or worse, are simply more consistent in how quickly they become themselves.

But what about those teams that take the scenic route to finding their identity? The ones that need 50, 60, or even 70 games?

Part IV: The Late Bloomer Effect

Conventional wisdom suggests that teams showing their true identity later in the season are probably struggling. After all, if you're still searching for who you are 50 games into an 82-game season, that can't be good... right?

Once again, the data tells a different story.

The pattern becomes clearer when we dig into the numbers. Of the 284 teams, since 1976, that needed more than 30 games to find themselves, about 56% finished with winning records. That percentage holds steady through 40 games, but then something interesting happens: teams needing 50 or more games jump to a 60.5% success rate. Push it to 70 games, and the success rate climbs to 61.4%.

Even more striking? Of the 22 teams that needed more than 80 games - basically the entire regular season - to establish their identity, 72.7% finished above .500. The longer a team takes to find itself, the more likely it is to end up successful.

This creates an interesting paradox in modern NBA team development. While good teams since 2014-15 typically show themselves quickly - around the 16-game mark - the teams that take the scenic route often end up just as successful, if not more so.

Take the 2022-23 Miami Heat, for instance. Despite returning their core of Jimmy Butler, Bam Adebayo, and Tyler Herro, they needed 49 games to consistently play at their eventual level. They started slowly, struggled with consistency, and were even under .500 at the halfway point. But once they found their stride? They finished strong, secured a play-in spot, and stormed through the playoffs all the way to the NBA Finals. Their journey shows how a talented team taking the scenic route to finding its identity can still reach its destination - and often end up better for the long development process.

Why would this be? There are a few possible explanations:

First, good teams have more room for improvement. A bad team playing badly is simply meeting expectations. But a good team playing below their capability has somewhere to grow.

Second, teams that take longer to find themselves might be more likely to be dealing with incorporating new pieces, implementing new systems, or adjusting to injuries. These are problems that winning teams are more likely to have the luxury of working through.

Finally, there's simple math: it's harder to maintain a losing record while playing well for long stretches, even if those stretches come late in the season. Teams that find their stride late are more likely to have climbed above .500 in the process.

This "Late Bloomer Effect" has implications for how we watch the NBA. But it also raises an important question: in an era where good teams are showing their identity faster than ever, is this pattern starting to change?

Part V: What This Means For Modern NBA Fans

So, what does all this mean when you're watching your team as we approach the quarter-mark of the season?

Let's start with some practical applications. If you're a Nuggets fan, history says you already know what you're watching - they typically show their identity by game 16. Same goes for Trail Blazers (17.5 games) and Bucks (17.6) fans. These franchises tend to reveal themselves early, for better or worse.

But if you root for the Pelicans (29.8 games), Bulls (28.3), or Hornets (27.5)? You might want to hold off on any definitive judgments until after the new year. These teams historically need more runway before showing their true identity.

The seasons since 2014-15 have given us an even clearer roadmap. When teams start strong and maintain it through 16-17 games, that's usually who they are. The days of good teams taking sometimes up to half a season to figure things out are largely behind us. Analytics, sophisticated player development systems, and modern coaching have accelerated how quickly winning teams establish themselves.

But here's the thing about struggling teams - they still need about 22 games to show their true identity, just like they always have. Sometimes much longer. Take last season’s Chicago Bulls. Despite having established stars in DeMar DeRozan and Zach LaVine, plus a future Second Team All-Defense player in Alex Caruso, it took them 64 games to consistently play at their eventual level. Even with modern analytics and development systems, the process of finding your identity can't be rushed. The tools might be better, but the fundamental challenge of building team chemistry remains as time-consuming as ever.

This creates some practical guidelines for watching early-season basketball:

If your team starts hot and maintains it through 16 games, trust it. The numbers suggest this is particularly true in recent seasons.

If your team is struggling, give them those traditional 22 games before making any firm judgments.

Know your franchise's history. Some teams consistently need more time than others.

When teams do take longer to find themselves (50+ games), they tend to end up on the winning side of the ledger more often than not.

The implications go beyond just fan patience. Front offices armed with sophisticated analytics can make trade deadline decisions with more confidence. Coaching evaluations have clearer benchmarks. Player development patterns are more predictable. But rebuilding teams still need that traditional runway - suggesting there might be a natural limit to how quickly teams can establish who they really are, even in the analytics era.

Looking at nearly half a century of NBA basketball has taught me something profound about team development. Despite all our modern tools - the tracking data, the analytics, the advanced metrics - we still can't fully predict or control how long it takes a team to become itself. Some teams, like the Nuggets, show us exactly who they are in the first month. Others, like those 2000-01 Bucks, need 75 games to figure it out. A few test our patience until the final weeks of the season.

And maybe that's exactly what makes watching basketball so captivating. In an era where we can measure and analyze everything, team development remains beautifully, frustratingly unpredictable.

Want to dig deeper? I've made the full dataset available here. The spreadsheet includes over 60 sheets of data, including:

Each franchise's "True Team" dates going back to 1976

Historical patterns by era, market size, and conference

Complete season-by-season breakdowns

All the data behind the analysis featured in this post

Find your team's sheet (labeled "True TEAM NAME") to see exactly when they showed their true identity each season in franchise history. You might be surprised by what you discover.

Have thoughts about your team's development patterns? Notice something interesting in the data I might have missed? I'm particularly curious to hear from fans of teams that consistently break the mold - whether they're quick developers like the Nuggets or late bloomers like the Pelicans.

I'm also collecting ideas for future deep dives into NBA statistics. Some questions I'm exploring:

Can True Team pinpoint when championship hangovers end?

Do playoff teams show their identity faster?

What happens in the seasons after teams find their identity extremely late?

Share your observations in the comments below, or if you're a subscriber, email boxscorebrain@substack.com with your suggestions for the next statistical oddity I should investigate.