Hockey's Radical Revolution: When the Game Finally Allowed Forward Passing

Before the 1930s, hockey players couldn't pass forward. The story of how this changed involves lumber barons, a tragic death, and a transformation that saved professional hockey.

Mention the "forward pass" to any sports fan and their mind immediately jumps to football. It's the innovation that transformed a grinding rugby-style game into the dynamic sport we know today. The story of how the forward pass saved football is practically legend at this point.

But there's another forward pass story that's just as fascinating - and far less known.

I discovered it by accident while watching a video about the neutral zone trap. The narrator casually mentioned that hockey once prohibited forward passing entirely. I had to rewind and watch that part again.

Wait, what?

Like most hockey fans, I'd taken the forward pass for granted. The idea that players once couldn't pass the puck ahead to teammates seemed absurd. How could the game even function? What about those perfect tape-to-tape passes through the neutral zone? Those beautiful stretch passes that spring forwards for breakaways?

The more I dug into this, the more fascinating the story became. Hockey's forward pass revolution wasn't just a simple rule change - it was a fundamental transformation that may have saved professional hockey itself. And surprisingly, the transition finished well before football fully made its famous change.

Consider this timeline:

1889: The Dartmouth Chebuctos demonstrate forward passing under Halifax Rules in Quebec City - an innovation that intrigues but fails to take hold

1906: Football legalizes the forward pass with severe restrictions - heavy penalties for incomplete passes, limited catching zones

1913: The Pacific Coast Hockey Association (PCHA) allows forward passing in the neutral zone

1929: The NHL fully adopts forward passing in all zones

1933: Football finally removes most forward pass restrictions

While football's story gets the glory, hockey actually pioneered the concept of opening up the game through forward passing, completing its transformation years before football fully embraced its own passing revolution.

This is the story of how hockey evolved from a static game where every pass had to go backward or sideways into the flowing, dynamic sport we know today.

It's a tale of innovative leaders, resistant traditionalists, and the radical idea that maybe - just maybe - letting players pass the puck forward might make the game more exciting.

By the time you finish reading this, I hope you'll think of hockey the next time someone mentions the forward pass. Because while football's forward pass story gets all the attention, hockey's version might be even more dramatic.

Part I: The Old Game

Step into a hockey arena in 1910, and you might not recognize the sport being played. Seven players crowd the ice - yes, seven - moving in intricate patterns that would seem alien to modern fans.

The game's very nature was different - not just in its rules, but in its fundamental philosophy. This wasn't just hockey before the forward pass. This was hockey when passing forward was considered unsportsmanlike.

The game prided itself on being a "scientific" pursuit, more like a chess match than the dynamic sport we know today. Each scoring attempt was a carefully choreographed sequence:

First, the center would gain control, surveying the ice like a quarterback

The wingers would weave intricate patterns, always moving backward or sideways

The rover - that crucial seventh player - would dart between layers of defense, creating confusion

The puck would move laterally and backward through this elaborate dance

Finally, after this complex buildup, one player would attempt to break through with a rush

They called this "combination play," and the best teams elevated it to an art form. A single scoring attempt might involve five or six backward passes, the puck zigzagging up ice in an elaborate pattern. The term "combination play" would gradually fade from hockey's vocabulary as the game evolved, but in 1910, it was the height of tactical sophistication.

Surprisingly, this methodical approach didn't result in low-scoring games. The 1917-18 season saw teams averaging 4.75 goals per game. The reason lay in equally rigid defensive formations - once a defender was beaten, there was little help behind them. A skilled puck carrier who broke through often found themselves one-on-one with a goalie who, by rule, couldn't leave their feet to make saves.

The result was a fascinating rhythm: long stretches of intricate passing followed by sudden, explosive individual rushes. Players like Joe Malone could dominate simply by mastering this pattern. Malone's record of seven goals in a single game, set in 1920, still stands today - a great example of how different scoring was in this era.

But tradition wasn't the only force preserving this style of play. Money played a crucial role. The National Hockey Association (NHA), predecessor to the NHL, had created a peculiar incentive structure: generous bonuses for goals, but minimal compensation for assists. The criteria for what constituted an assist were kept intentionally strict to limit payouts.

Forward passing threatened this financial model. Team owners, watching their bottom line, worried that it would lead to more assists and higher bonus payments. Some likely estimated their payroll costs could double or triple if passing forward became legal.

This complex web of tradition, pride, and financial interests stood firmly against change. Hockey had built itself around the idea that moving backward was the only honorable way forward. But in the far west, two brothers were about to challenge everything about how the game was played...

Part II: The Brothers Who Reimagined Hockey

Sometimes the biggest changes in sports come from unexpected places. In 1911, two brothers sold their family's timber interests in British Columbia. Instead of reinvesting in lumber, Lester and Frank Patrick did something else: they built an entirely new vision of hockey from the ground up.

It would change the sport forever.

The timing couldn't have been more critical. Hockey in 1911 was at a crossroads. The sport had spread across Canada and was beginning to take root in the United States, but its rigid playing style threatened to limit its appeal. The game needed to evolve, but the established eastern leagues were too set in their ways to embrace radical change.

The Patrick brothers weren't just wealthy businessmen with a hockey dream - they were uniquely positioned to revolutionize the sport. Everything about their background and situation made them perfect catalysts for change:

Both brought analytical minds to hockey's problems

Both were elite players, with Lester having won two Stanley Cups with the Montreal Wanderers

Their geographic isolation from eastern hockey likely freed them from traditional constraints

Most importantly, they controlled every aspect of their new league's operations

The brothers complemented each other perfectly. Frank was the visionary, always pushing for radical changes - he would eventually introduce 22 rule changes that remain in the NHL today. Lester was more cautious but brilliant at implementation. When Frank proposed forward passing in the neutral zone, Lester's initial response was telling: "I am not greatly in favour of the new offside rule," he told The Province in December 1913, "and will have to be shown where this rule will benefit the game before I will lend my support." Together, despite their different approaches, they created what amounted to a laboratory for hockey innovation: the Pacific Coast Hockey Association (PCHA).

The league was a completely new approach to hockey. Under the Patricks' guidance, innovation became the norm:

Built the first artificial ice rinks in Canada, allowing year-round play

Created the modern blue line system to organize the game into zones

Allowed goalies to leave their feet to make saves, revolutionizing goaltending

Developed a playoff system that would later become standard across hockey

Each of these innovations was met with skepticism from the traditional hockey establishment. The Patricks had something other hockey leagues didn't: complete control over their product and a willingness to experiment.

In 1913, the Patricks made their boldest move yet. The PCHA would allow forward passing in the neutral zone. Eastern hockey authorities were horrified. The Toronto Daily Star declared it "an absurd rule... as the teams will discover as the season progresses."

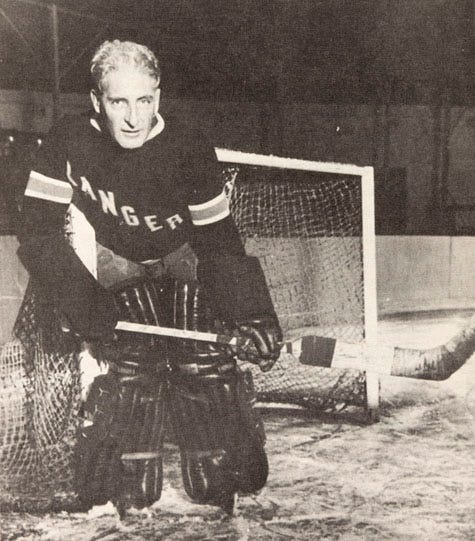

But the Patricks had a secret weapon: Fred "Cyclone" Taylor, a player whose talents seemed to come from hockey's future rather than its past. Taylor could skate backward as fast as most players skated forward, his stick handling left defenders bewildered, and he moved through space with an almost supernatural understanding of where everyone on the ice would be. Most importantly, he had a theatrical flair that drew crowds - exactly what the Patricks' new league needed.

In the traditional game, Taylor was like a Ferrari forced to drive in first gear. The requirement to always pass backward confined his creativity and limited his ability to read and exploit open ice. The Patricks saw something others missed: with forward passing, Taylor could become hockey's first modern superstar.

The transformation was immediate. In the 1913-14 season, playing under the new forward passing rules, Taylor didn't just improve - he reinvented what was possible on ice. His 24 goals in 16 games more than doubled his scoring rate from the previous year. But the numbers only told part of the story. Taylor was playing a different sport entirely, one that looked more like modern hockey than the methodical game of his era.

The Stanley Cup, hockey's ultimate prize, wasn't yet exclusive to one league. Each year, the champions of the eastern (NHA/NHL) and western (PCHA) leagues would meet to determine the true champion of hockey. These finals became hockey's greatest laboratory. For the first time, fans could directly compare the old and new versions of the sport on consecutive nights. The same players, the same ice, but two radically different games. The contrast was impossible to ignore - games played under PCHA rules were faster, higher-scoring, and more exciting.

Because neither league would fully yield to the other's rules, the finals alternated between:

PCHA rules (forward passing allowed in neutral zone)

Eastern rules (no forward passing)

The 1915 Stanley Cup Finals drove this point home when the Vancouver Millionaires, using the forward pass, dominated the Ottawa Senators to win the Cup.

Two years later, the Seattle Metropolitans became the first American team to win the Stanley Cup, also using PCHA rules.

The writing was on the wall.

By 1918, the eastern resistance to forward passing began to crumble. The NHL cautiously dipped its toe in the water, allowing forward passing in the neutral zone only. But this half-measure would prove more dangerous than no change at all. For the next decade, hockey would exist in an awkward limbo - neither fully embracing its future nor completely holding to its past.

The Patrick brothers had lit the fuse of revolution with their lumber fortune. But innovation can be dangerous when implemented halfway. The transformation they started would exact a terrible price before it was complete - one measured not just in declining attendance and fan interest, but in the life of Montreal defenseman Joe Hall.

Part III: The Transformation

The forward pass experiment had created an uncomfortable reality in professional hockey by 1919. Two distinct versions of the sport now existed side by side: the PCHA's more open, pass-oriented game in the West, and the NHL's traditional style in the East. This split became most apparent - and most dangerous - during championship play.

The problem wasn't just philosophical. It was physical. Teams of the era operated with skeleton crews by modern standards:

Most clubs carried only 8-10 players total

Substitutions were rare, seen as a sign of weakness

Players regularly logged 50-60 minutes of ice time per game

Training methods hadn't evolved to match the game's increasing demands

When eastern and western teams met, they were essentially asked to master two different sports on alternating nights. Players had to constantly readjust their muscle memory, tactical understanding, and physical positioning. The strain was immense, but few recognized the looming danger.

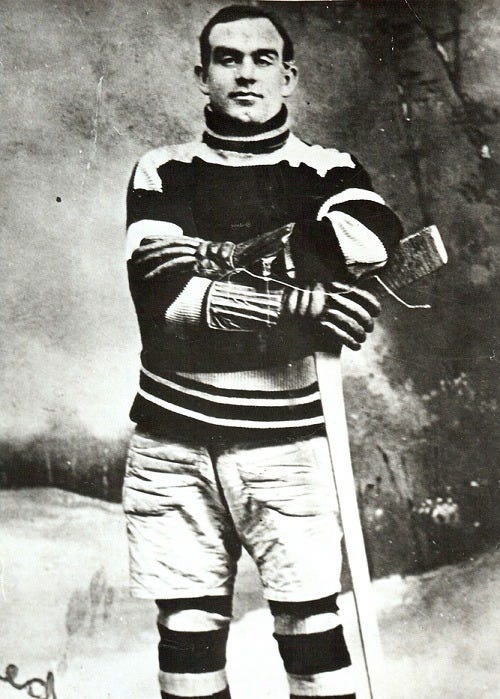

The 1919 Stanley Cup Finals between the Montreal Canadiens and Seattle Metropolitans would expose these contradictions in tragic fashion. Montreal arrived with just nine players. Seattle had only eight - a situation made worse by the absence of their star player Bernie Morris, who was in jail facing military desertion charges. What followed was a brutal test of human endurance that pushed athletes beyond their breaking point.

By Game 4, the physical toll became catastrophic. After regulation ended scoreless, Seattle's Cully Wilson collapsed from exhaustion during overtime. Other players were literally staggering on the ice. Officials called an unprecedented tie when players could no longer continue.

Game 5 pushed human endurance even further. Seattle built a 3-0 lead but their exhausted players couldn't maintain it. Montreal, using superior size, overwhelmed the depleted Metropolitans to force Game 6.

Then disaster struck.

The Spanish Flu, which had been ravaging the global population, found perfect hosts in the physically depleted players. The grueling physical demands of the series, exacerbated by the unusual format and the limited number of players, left the athletes vulnerable.

Joe Hall, Montreal's defenseman, collapsed with a 105°F fever. Five other Canadiens were hospitalized. Seattle's Roy Rickey fell critically ill.

On April 5, 1919, Joe Hall died. For the first and only time, the Stanley Cup was not awarded. The engraving tells the story simply: "Series Not Completed" - a blank space in hockey history that would only be matched once more, when the 2004-05 NHL lockout left another season without a champion.

Despite the stark warning written in the Stanley Cup's blank engraving, hockey's leadership seemed determined to learn its lessons the hard way. Rather than choosing a clear direction, the sport stumbled forward with its dangerous experiment in partial forward passing. The consequences would take another decade to fully unfold.

By the late 1920s, the situation had reached a crisis point. The once-exciting game had devolved into a defensive, possession-based slog. A typical game might see teams passing laterally for minutes at a time in their own zone, waiting for the perfect moment to advance. When they did move forward, they'd often retreat at the first sign of resistance rather than risk losing possession. What had once been a game of skilled rushes and tactical innovation had become an exercise in cautious attrition. The numbers told a stark story: scoring had fallen from 4.79 goals per game in 1919-20 to a meager 1.46 goals per game in 1928-29. Fans were growing weary of the unwatchable games, and the NHL's future was at stake.

Ironically, the partial forward pass rules had made hockey less dynamic than it had been in the pre-forward pass era. Teams had adapted to the restrictions, developing strategies that stifled creativity and limited scoring chances. The game's very essence was in danger of being lost.

When hockey finally embraced its future in 1929, the changes went beyond just allowing forward passing in all zones. The sport at last confronted the deeper issues that had contributed to the 1919 tragedy: rosters expanded, regular substitutions became standard practice, coaches developed line shift systems, training methods evolved for endurance, and equipment adapted for faster play.

The impact was immediate - almost too immediate. The surge in scoring was so dramatic that by December 1929, just months after allowing forward passing in all zones, the NHL had to implement new restrictions to maintain competitive balance.

The tactical revolution was equally dramatic. The methodical "scientific game" disappeared, specialized player roles emerged, teams developed systematic approaches, modern power play concepts were born, and new defensive systems countered speed.

Hockey had become something entirely new. Centers were playmakers, not just puck carriers, defensemen joined the rush, wingers needed speed and anticipation, the game was faster and more dynamic, and team play replaced individual excellence. The transformation that began with the Patrick brothers' experiment, proved its dangers in 1919, and reached crisis point in 1928, was finally complete. Hockey had evolved into its modern form.

Indeed, the echo of this transformation would shape hockey's development for the next century.

Part IV: Legacy and Lessons

Every time you watch an NHL game, you're witnessing the living legacy of hockey's forward pass revolution. That lightning-quick transition from defense to offense? The power play's intricate passing sequences? All of these elements of modern hockey trace directly back to the transformation of the late 1920s.

The revolution's fingerprints are everywhere in today's game. When the Tampa Bay Lightning deployed their lethal 1-3-1 power play, they were building on principles first discovered in 1929, when teams realized forward passing could pull penalty killers out of position. When Colorado Avalanche star Nathan MacKinnon explodes through the neutral zone, he's utilizing space in ways Cyclone Taylor first envisioned a century ago. Even the notorious neutral zone trap that made the New Jersey Devils infamous in the 1990s evolved from defensive adaptations first developed to counter forward passing.

This transformation didn't just change specific plays - it revolutionized every aspect of hockey strategy. The stretch pass became a systematic weapon for beating defensive schemes. The power play evolved from static formations into a dynamic dance of passing lanes and one-timer opportunities. Defensive systems transformed from simple coverage into complex layers of support and gap control.

Yet perhaps the most profound legacy is how the forward pass revolution continues to shape hockey's evolution. As the NHL debates modern changes - bigger nets, hybrid icing, stricter equipment regulations - the arguments echo those from 1929. The same concerns about tradition, the same fears about fundamentally changing the game, the same tension between evolution and preservation.

The pattern is familiar: first comes resistance, then careful experimentation, then unexpected consequences, and finally adaptation into a new normal. We saw it with curved sticks, with regular line changes, with video review. Each innovation initially faced claims that it would "ruin hockey" - just as they once said about the forward pass.

When you watch an NHL game today, look for the ghosts of 1929: every tape-to-tape breakout pass, every give-and-go play, every cross-ice one-timer exists because hockey once dared to fundamentally change its nature. The forward pass didn't just change hockey - it saved it. Without this transformation, the sport might have remained too complex and static to capture widespread appeal. Instead, it evolved into one of the world's most dynamic team sports.

The lesson is clear: sometimes preserving a game's essence means being brave enough to change its fundamentals.

Part V: Closing Thoughts

When I opened this story, I noted that most sports fans think of football when they hear "forward pass." But hockey's forward pass revolution tells us something more profound about how sports evolve - and sometimes must evolve to survive.

The transformation represented a fundamental choice about hockey's future: remaining a fairly niche sport or evolving into a dynamic game capable of capturing the world's imagination. The Patrick brothers reimagined what hockey could be. The tragedy of 1919 didn't just claim Joe Hall's life; it forced the sport to confront its resistance to change. The scoring crisis in the late 1920s didn't just push hockey to fully embrace forward passing; it showed how half-measures often prove more dangerous than bold change.

Today's NHL faces similar crossroads: how to make the game safer without sacrificing excitement, how to increase scoring while preserving skill, how to use technology without losing spontaneity, and how to evolve while honoring tradition. The forward pass story teaches us that these aren't really choices between progress and tradition. They're choices between evolution and stagnation.